Simulating mechanical forces

Meshes and microstructure¶

Cylindrical domain¶

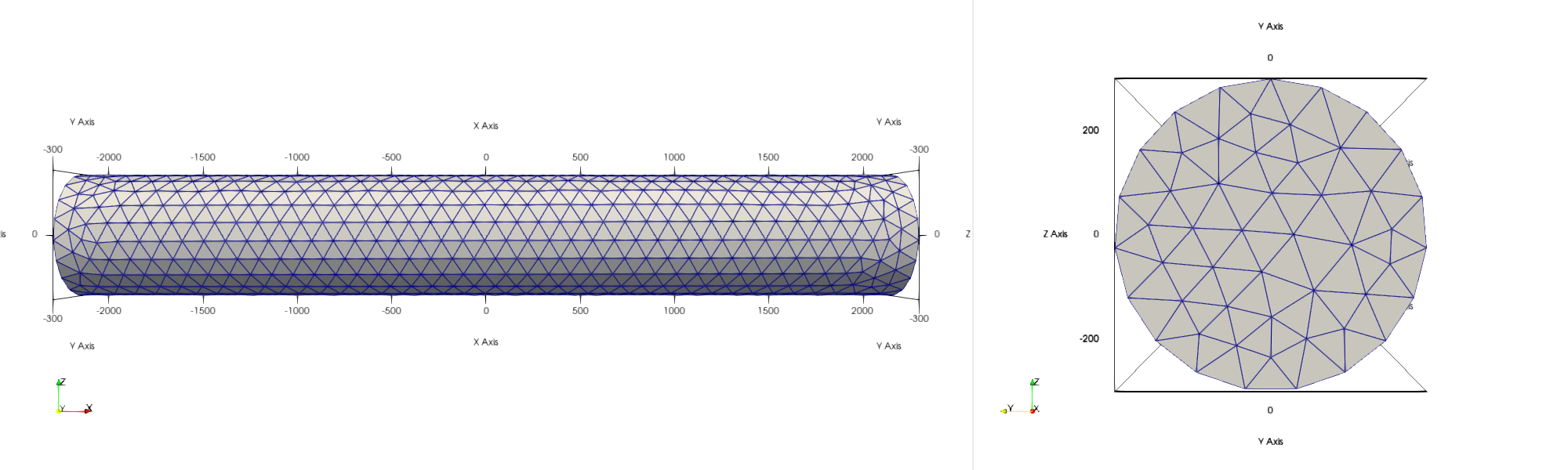

We consider a cylindrical domain with

We let and and will refer to as

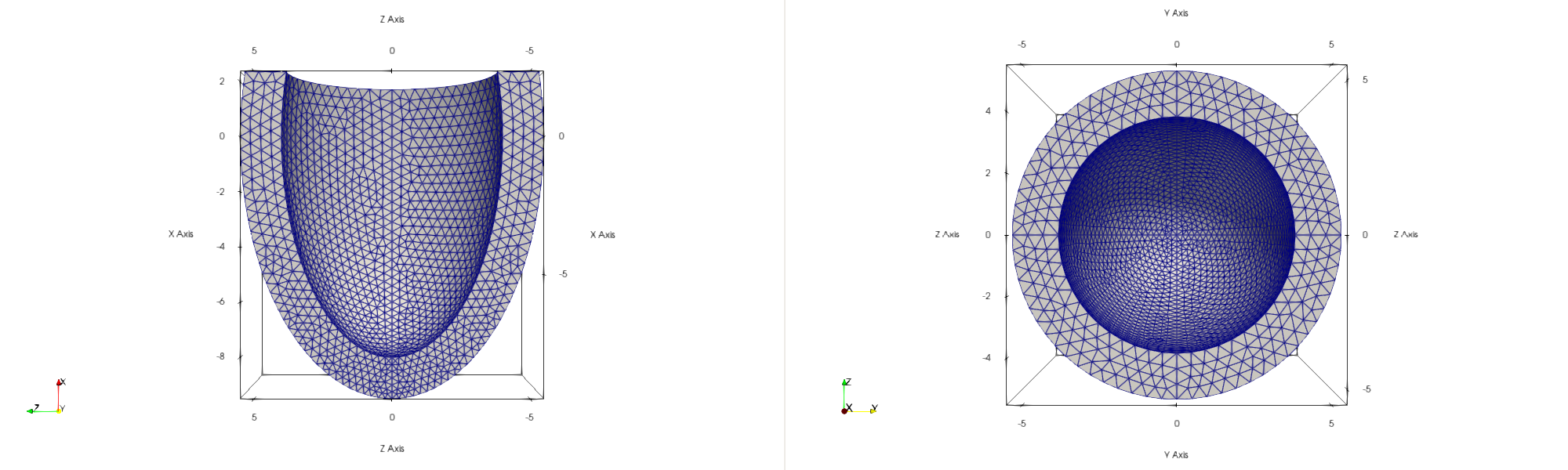

Figure 1:Cylindrical mesh with and

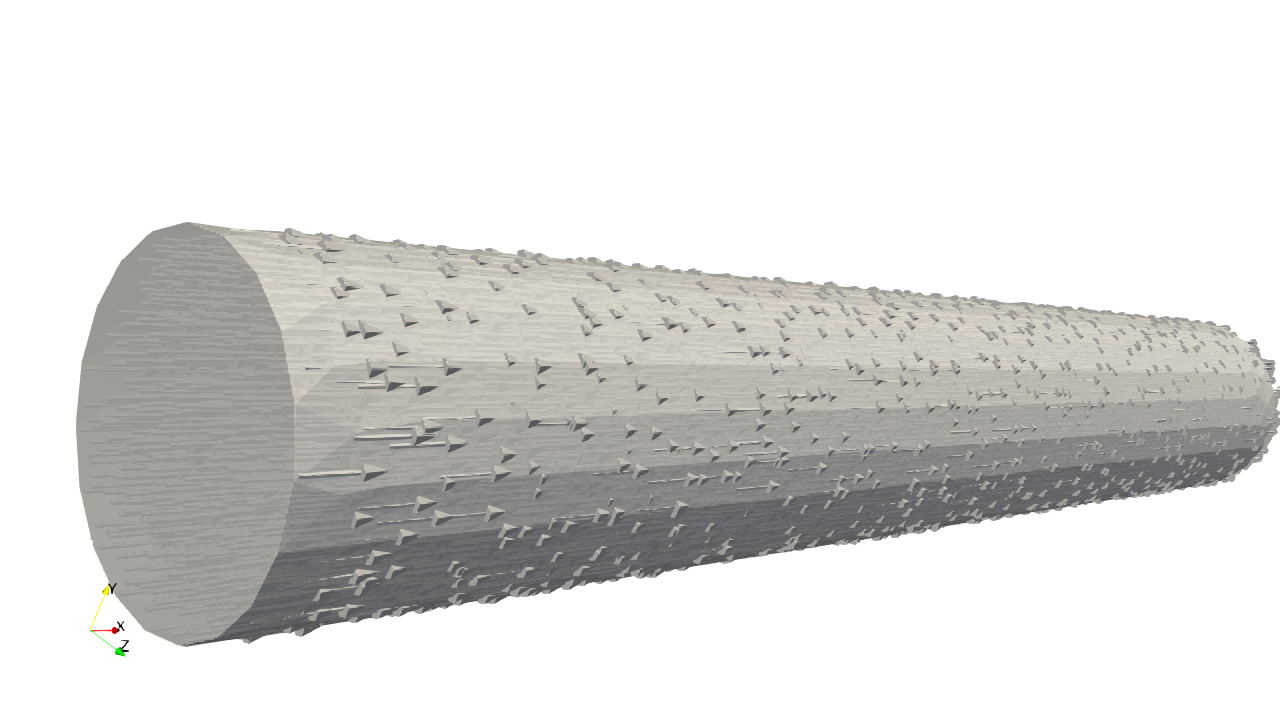

For the cylinder we also define a local coordinate system in the longitudinal (aka fiber) direction

In our case we orient the fibers along the height the cylinder, i.e

Figure 2:Showing the orientation of the cardiac fibers for the cylinder along the longitudinal direction

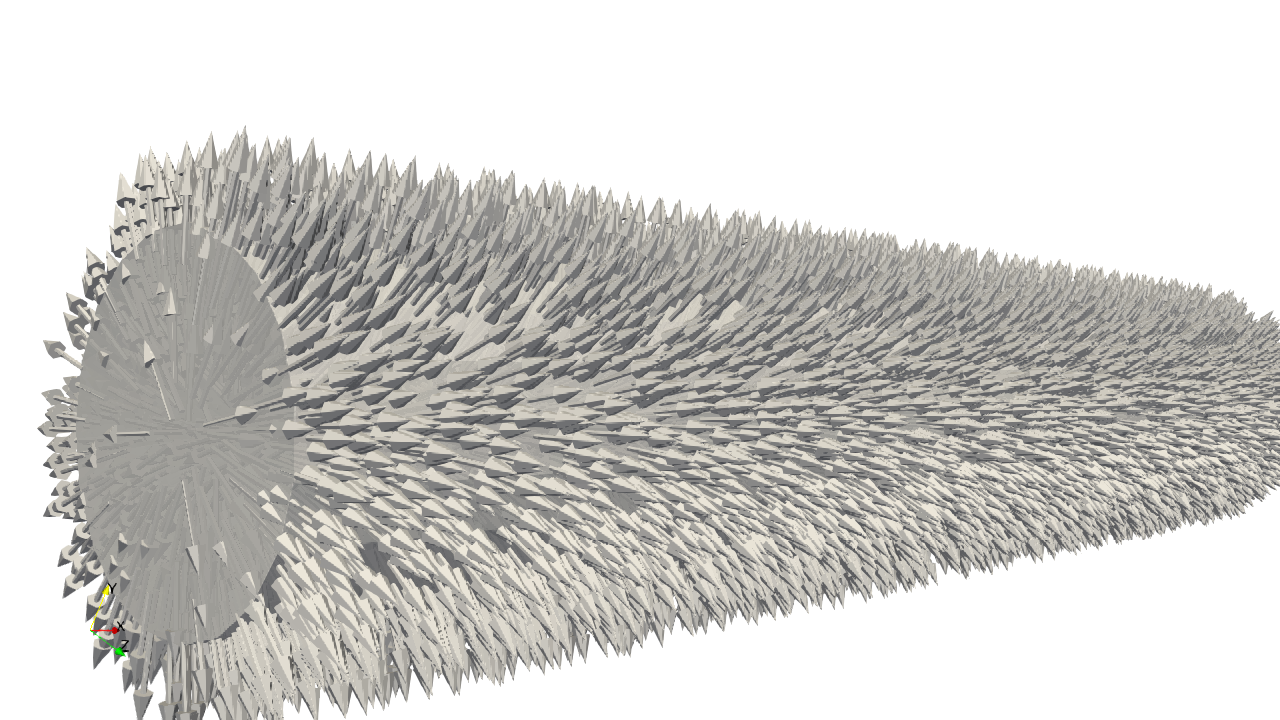

In a cylinder there is a natural decomposition into radial and circumferential components. We have the radial basis function given by

Figure 3:Showing the orientation of radial components

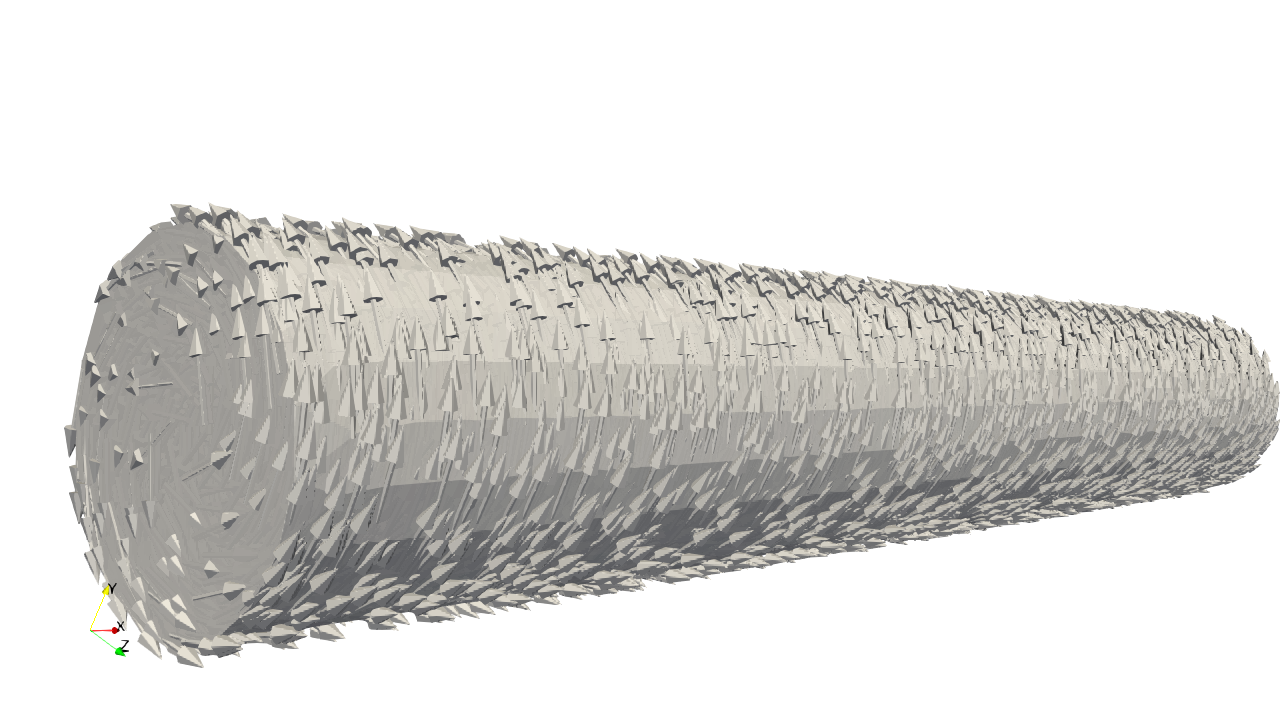

and the circumferential basis function given by

Figure 4:Showing the orientation of circular components

LV domain¶

We will also test out an idealized LV domain generated using cardiac-geometries

Figure 5:Idealized LV mesh with width of 1.5 mm, a short axis radius of 4 mm and a long axis radius of 8 mm.

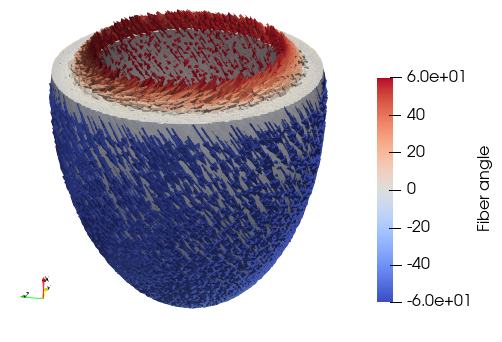

For the LV we also have the rule based fiber orientations

Figure 6:Fiber orientations in the LV with and endo / epi fiber angle of 60/-60.

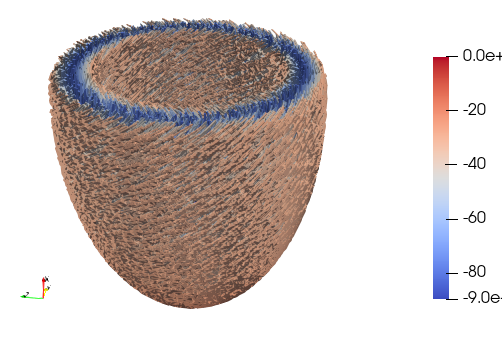

Figure 7:Sheet orientations in the LV.

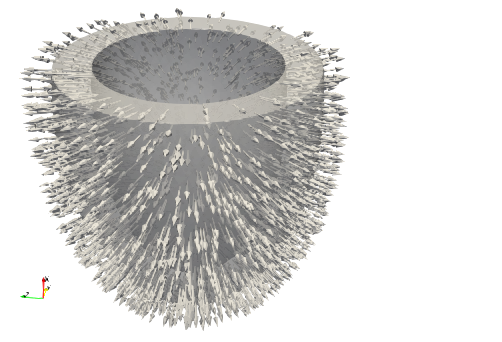

Figure 8:Sheet-normal orientations in the LV.

Material model¶

We use the the transversely isotropic version of the Holzapfel Ogden model, i.e

with

and

is the Heaviside function. Here

and

and

with being the direction the muscle fibers.

Material parameters¶

The material parameter are

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| 2280 Pa | |

| 9.726 | |

| 1685 Pa | |

| 15.779 |

Modeling of compressibility¶

Modeling of active contraction¶

Similar to Finsberg et. al we use an active strain formulation and decompose the deformation gradient into an active and an elastic part

with

In these experiments we use to represent end systole.

Variational formulation¶

We model the myocardium as incompressible using a two field variational approach and finite elements for the displacement and hydrostatic pressure . m

The Euler‐Lagrange equations in the Lagrangian form reads: find such that for all we have

For the cylinder we have

where represents the boundaries at each end of the cylinder. Here we enforce a Robin type boundary condition at both ends of the cylinder with a spring . This parameter will be used to represent the loading conditions and we choose 1 Pa / μm to represent standard loading conditions.

For the left ventricle we have

Here we enforce a Robin type boundary condition at the epicardium, , with a spring kPa / mm, and an endocardial pressure on the endocardium . In addition we fix the basal plane in the longitudinal direction.

Cauchy stress¶

The Cauchy stress tensor is given by

We can extract different components of the Cauchy stress tensor. For example the fiber component can be extracted using the following formula

where is the vector field displayed in Figure 6 in the current configuration.

Numerical experiments¶

Cylinder¶

For the experiments with the cylinder we simulated two states; one relaxed state and one contracted state. For the contracted state we used

Cylinder varying spring¶

We tested different values of the spring constant , with Pa / μm, representing standard load, Pa / μm representing unloaded and kPa / μm representing increased load.

Figure 9:Resulting diameter at the center for the cylinder in relaxed and contracted state for spring constants

Figure 10:Resulting length of the cylinder in relaxed and contracted state for spring constants

Figure 10:Fractional shortening

Figure 12:Resulting strain the cylinder in the contracted state for different spring constants in the longitudinal , circumferential and radial direction

Figure 13:Resulting stress the cylinder in the contracted state for different spring constants in the longitudinal , circumferential and radial direction

Figure 13:Resulting deviatoric and hydrostatic stress the cylinder in the contracted state for different spring constants in the longitudinal , circumferential and radial direction

Twitch¶

To simulate twitch we create a syntetic curve for γ,

and

Figure 15:Resulting diameter at the center for the cylinder in relaxed and contracted state for spring constants

Figure 16:Resulting length of the cylinder in relaxed and contracted state for spring constants

Figure 16:Fractional shortening

Figure 18:Resulting stress the cylinder in the contracted state for different spring constants in the longitudinal , circumferential and radial direction

Figure 19:Label corresponding to figure Figure 18 showing which regions we average the stress

LV¶

For the LV we have two different states; one where we have no endocardial pressure (referred to as the unloaded state) and one where we apply an endocardial pressure of 15 kPa (referred to as the loaded state). In both cases we set .

Figure 20:Strain in the fiber, sheet and sheet normal direction for the unloaded and loaded state

Figure 21:Stress in the fiber, sheet and sheet normal direction for the unloaded and loaded state

Figure 21:Stress in the fiber, sheet and sheet normal direction for the unloaded and loaded state

- Holzapfel, G. A., & Ogden, R. W. (2009). Constitutive modelling of passive myocardium: a structurally based framework for material characterization. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 367(1902), 3445–3475. 10.1098/rsta.2009.0091

- Finsberg, H., Xi, C., Tan, J. L., Zhong, L., Genet, M., Sundnes, J., Lee, L. C., & Wall, S. T. (2018). Efficient estimation of personalized biventricular mechanical function employing gradient‐based optimization. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Biomedical Engineering, 34(7). 10.1002/cnm.2982